SLAC Partners with Small Businesses to Put Technology to Good Use

Researchers at SLAC collaborate with small businesses to develop technology so it can benefit the world at large.

Even the cleverest invention is no good if no one gets to use it – and even the most useful invention may need a lot of tweaking to operate at its best. That’s why researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory collaborate with small businesses to develop technology so it can benefit the world at large.

Right now they’re working on:

- Improving the performance of a compact, SLAC-invented accelerator that generates intense X-rays for medical imaging, materials science and other applications.

- Making it easier for scientists to operate an X-ray microscope that’s critical for research here and around the world.

- Exploring ways to make radiofrequency (RF) cavities sturdier, more perfect and more efficient at accelerating particles, paving the way for smaller and cheaper accelerators for science, medicine and industry.

All three are funded by the DOE Office of Science through two programs – Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) – that award contracts to small companies, which often work with scientists at DOE national labs on projects of mutual interest. The Office of Science just released the list of topics for its next round of SBIR and STTR funding, with applications due Oct. 14.

“We look for proposals that take our technology out into the world or help develop something that’s of important use to us, as well as to the broader community,” says Mark Hartney, SLAC’s director of strategic planning. The goal, he says, is to make each project a win-win for both partners by leading to new products and innovations.

“SLAC provides facilities that a small business certainly can’t afford, allowing you to come up with innovative technologies and verify them with high-power testing,” said R. Lawrence Ives, president of Calabazas Creek Research in San Mateo, California, which is partnering with SLAC on the acceleration cavity project. “And of course we take advantage of SLAC’s expertise.”

Lyncean: Commercializing a Compact X-ray Source

The compact X-ray source is a case in point.

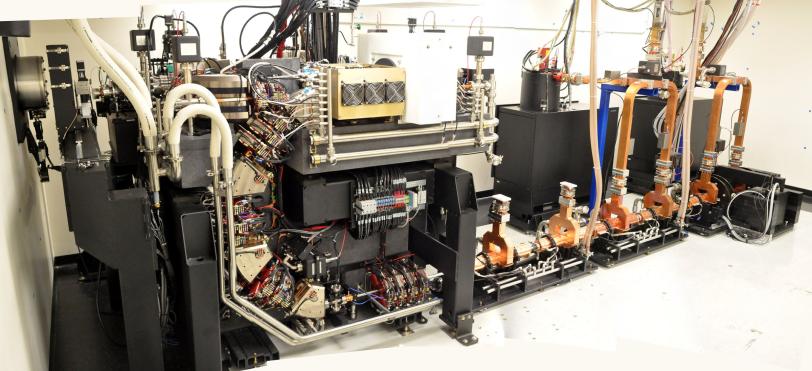

While working on basic accelerator technology at SLAC, three researchers invented a way to shrink synchrotrons – electron accelerators that generate intense X-ray beams – from the size of a stadium to the size of a small car. Since these X-ray sources have a wide range of applications in medicine, biology, materials science and other fields, miniaturizing the technology could have a huge impact. Stanford and SLAC patented the little synchrotron, and in 2002 the inventors founded Lyncean Technologies in Palo Alto, California, to turn it into a commercial product. They plan to deliver the first model to the Center for Advanced Laser Applications in Germany this fall.

With funding from an SBIR grant, four researchers from the SLAC Accelerator Directorate are helping Lyncean’s core technical staff improve the machine’s performance.

“I know these guys are top-notch,” said company co-founder Rod Loewen. “The system is small but it’s complicated, and we knew it could benefit from building custom solutions using the knowledge SLAC has.”

He said he especially appreciated the DOE’s fast-track approval process, which allowed Lyncean to apply for two phases of funding totaling $1.1 million at once, and took just four months.

“The grant money helps pay for technology development for very specific improvements in electron beam performance – for example, we want a brighter, more intense electron beam and X-rays that are 10 times more intense,” Loewen said. “If we didn’t have the grant, a lot of this technology development would be a lot slower.”

Xradia/ZEISS: Sharpening a Scientific Tool

The X-ray microscope project is based on equipment invented by Xradia, then a small Pleasanton, California firm, and installed in 2006 at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light Source (SSRL), a DOE Office of Science user facility.

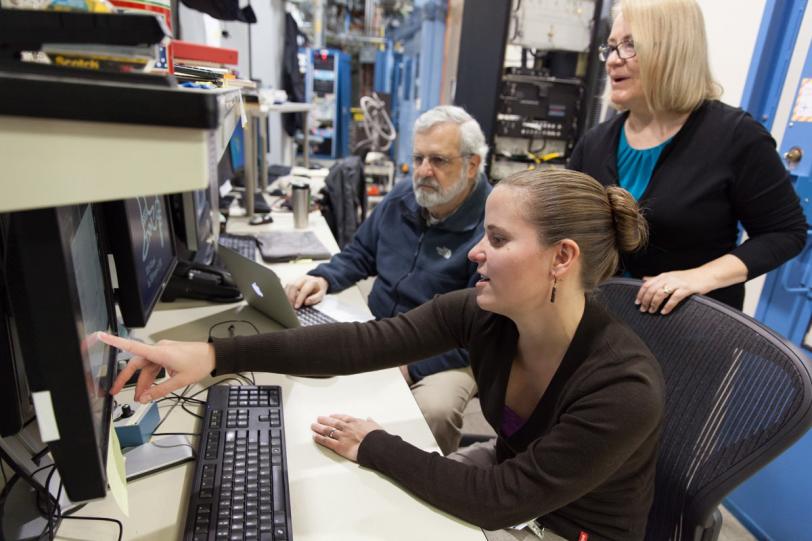

“We’re using this microscope to watch batteries while they’re charging and discharging and catalysts while they’re operating. We’re getting nanoscale information in real time so we can understand what’s working and what’s not,” said SSRL Staff Scientist Joy Andrews. She said Xradia, which was recently acquired by ZEISS, has been a “terrific partner” in optimizing how the microscope works.

Now, under a $150,000 Phase I STTR contract approved before the company’s acquisition, a consultant for the company is helping to streamline software used to automate the microscope’s operation so it’s easier for scientists to collect images.

“The idea for this software came from SSRL. They realized they had a need, and they needed it so badly they started their own development,” said Benjamin Hornberger, senior product marketing manager for what is now Carl Zeiss X-ray Microscopy in Pleasanton. “We’re basically taking their idea, and if there is any inefficiency in the software we’re taking care of it.”

The result, he said, benefits not only SSRL users and the company, which will sell the software, but also hundreds of scientists who use the company’s X-ray microscopes at light sources around the world.

“We want to make our customers successful,” Hornberger said, and when it came to improving this important research tool, “It made more sense to do it together.”

Calabazas Creek: Better Cavities for Faster Acceleration

The Calabazas Creek project stands to benefit high-energy physics experiments, free-electron lasers and other projects that use RF cavities to accelerate particles, including the International Linear Collider, the Compact Linear Collider, European XFEL and, potentially, future facilities at SLAC.

“One way of making RF accelerators less expensive is to make them shorter,” Ives said, “and the best way to do that is to develop cavities that support higher electric fields so they accelerate particles in a shorter distance. Increasing the fields by 5 or 10 percent doesn’t sound like much, but if your accelerator is 30 kilometers long, that’s millions of dollars’ worth of savings.”

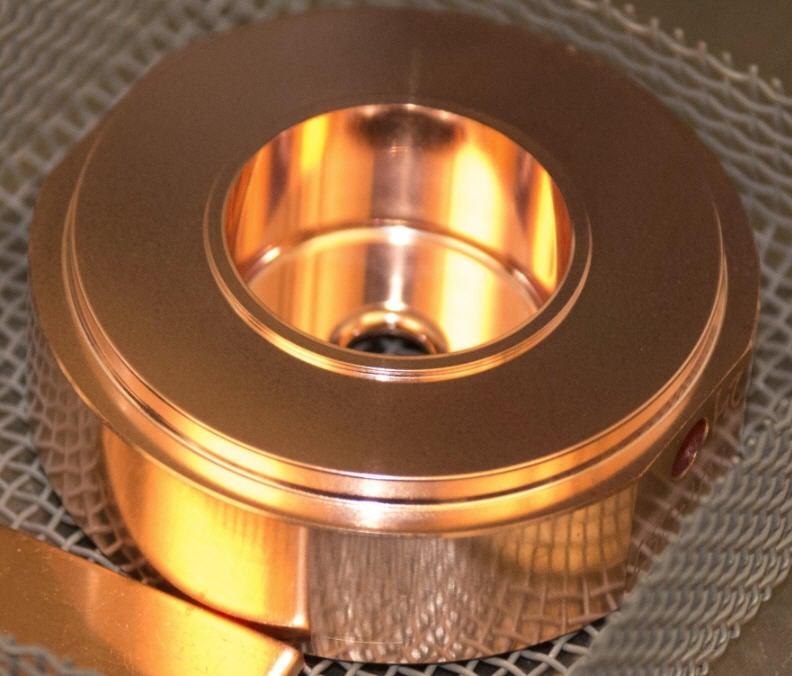

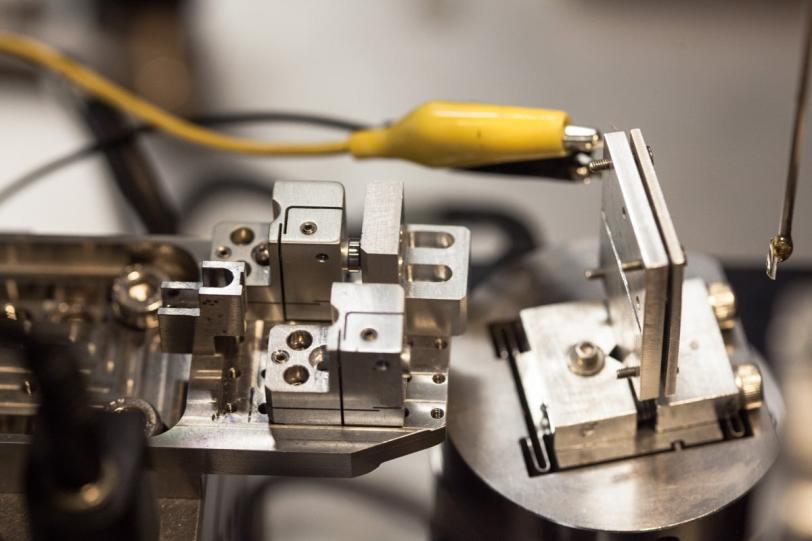

The problem is that today’s cavities can’t handle higher electric fields without breaking down. After discussing with SLAC researchers the potential for coating the inner surfaces of the copper cavities with an extremely thin, perfect layer of metal such as tungsten or platinum, Calabazas Creek was awarded a $150,000 SBIR contract to pursue the development. SLAC researchers are collaborating on the research and providing valuable guidance on coating parameters, as well as high power testing.

The cavities are being coated at a lab at North Carolina State University, and will be brought to SLAC for testing at one of the klystron test stations in the High Power Test Laboratory.

The coating technique, called atomic layer deposition or ALD, was developed for the semiconductor industry, Ives said. “ALD allows you to deposit materials on other materials one atomic monolayer at a time,” he said. “It’s the finest control you can possibly get.”

The hope is that these coatings will make the relatively soft copper cavities harder and more durable without degrading their electrical properties. “Whether or not it improves the performance remains to be seen,” Ives said, but the test results should help scientists understand the physics behind cavity breakdown and how it can be avoided.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.